Time to Get Your Swole On

<!-- /* Font Definitions */ @font-face {font-family:"Cambria Math"; panose-1:2 4 5 3 5 4 6 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:roman; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-536870145 1107305727 0 0 415 0;} @font-face {font-family:Calibri; panose-1:2 15 5 2 2 2 4 3 2 4; mso-font-charset:0; mso-generic-font-family:swiss; mso-font-pitch:variable; mso-font-signature:-1610611985 1073750139 0 0 159 0;} /* Style Definitions */ p.MsoNormal, li.MsoNormal, div.MsoNormal {mso-style-unhide:no; mso-style-qformat:yes; mso-style-parent:""; margin:0in; margin-bottom:.0001pt; mso-pagination:widow-orphan; font-size:12.0pt; font-family:"Times New Roman",serif; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri;} .MsoChpDefault {mso-style-type:export-only; mso-default-props:yes; font-size:10.0pt; mso-ansi-font-size:10.0pt; mso-bidi-font-size:10.0pt; font-family:"Calibri",sans-serif; mso-ascii-font-family:Calibri; mso-fareast-font-family:Calibri; mso-hansi-font-family:Calibri;} @page WordSection1 {size:8.5in 11.0in; margin:1.0in 1.0in 1.0in 1.0in; mso-header-margin:.5in; mso-footer-margin:.5in; mso-paper-source:0;} div.WordSection1 {page:WordSection1;} --> Blood Flow Restriction - A Five Minute Read

Blood flow restriction, “BFR”, occlusion training, hypoxic training, KAATSU—just a couple of different names for a training technique that is becoming increasingly popular in both the strength and conditioning and rehabilitation worlds.

What Is It?

Blood flow restriction is a training technique utilized to partially restrict blood flow during exercise, causing blood to pool in the limb. When BFR is combined with low load resistance training (20-40% 1RM) it produces increases in muscle size and strength, like the effect observed with high load resistance training (Scott et al., 2014). BFR is a technique used to create the necessary metabolic stress required to promote physiological changes without the same mechanical stress on the body (cool!).

How does it work?

To train using BFR it involved wrapping a pressure cuff around the top portion of a limb (upper arms if performing upper body exercises, and upper thigh if performing lower body exercises), to restrict blood flow out of the working muscle. When utilized appropriately arterial blood flow (blood leaving the heart and running TO the muscle) can enter the exercising muscle, but venous outflow (or the blood leaving the muscle to return to the heart) is restricted (Loenneke et al., 2014).

While the underlying physiology is not completely understood, there are a few proposed mechanisms for how BFR promotes skeletal muscle hypertrophy. First is the that when metabolic byproducts are contained in the muscle it produces a more acidic environment and initiates anabolic metabolism. This change in cellular environment increases the amount of growth hormone and IGF-1 which have a direct impact on protein synthesis, stimulating muscle hypertrophy (growth). Additionally, BFR has been thought recruit type II muscle fibers more rapidly, reversing how our body would volitionally recruit muscles per Henneman’s size principle. It may also increase the activation and number of myogenic stem cells, enhancing the overall hypertrophic response (Nielsen, 2012). While more research is underway to establish exactly what is occurring at the cellular level, the basic idea is that occluding blood flow allows individuals to train with lower weights and see the same strengthening results with less mechanical stress to the body.

Why do we care?

BFR has frequently been used in strength and conditioning programs to help healthy individuals maximize their strength, however, the argument for using this technique in a rehabilitation setting is particularly compelling. This process of creating an anabolic environment within the muscle to promote physiological adaptations usually only occurs during high intensity and high volume strength training. The problem is that high intensity and high volume strength training are not always an option in certain populations and have other inherent risk associated due to the mechanical stress on the body.

Typically, in strength training one must lift at least 70% of their 1RM to promote muscle hypertrophy, however, an athlete following surgery or an elderly individual who has been immobilized after a fall will likely not be able to lift at such a high intensity. BFR has been shown to reduce muscle atrophy seen with cast immobilization and has been shown to limit functional declines in muscular strength (Kubota et al. 2011). This is encouraging in the rehab setting because it can be utilized to promote changes in skeletal muscle using reduced loads to comply with tissue healing after surgery, helping individuals build strength and recover faster (Ozaki et al., 2011).

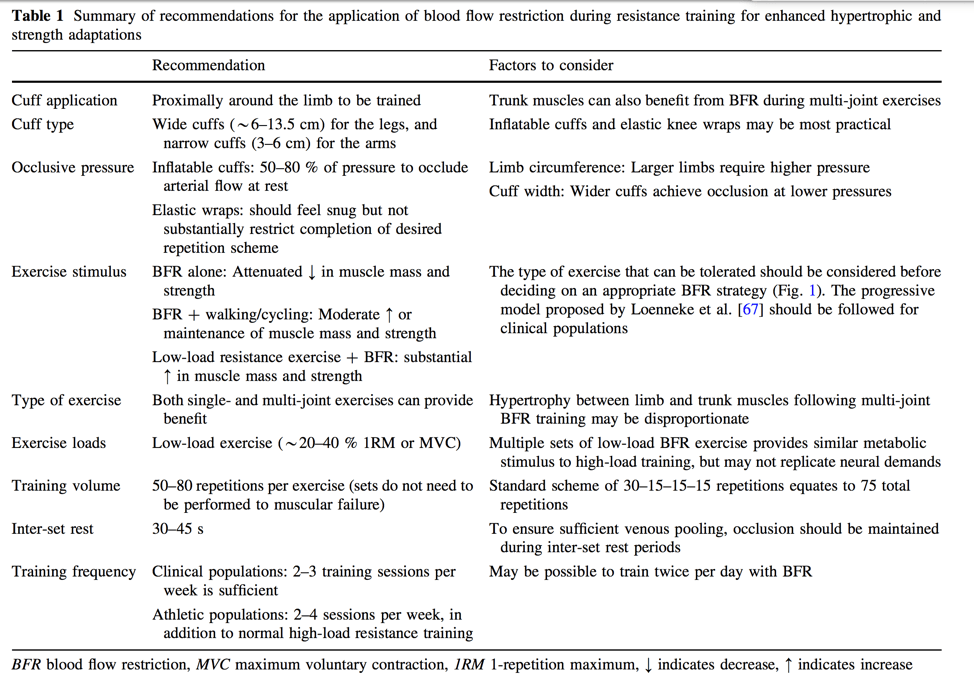

Cuff application:

In general wider cuffs have been shown to increase rating of pain with exercises and restrict arterial blood flow at lower pressures compared to narrow cuffs (Loenneke et al., 2012). Generally, try to use a cuff that is as wide as possible requiring less pressure to reduce arterial inflow.

-Upper extremity: proximal to the biceps muscle belly, just below the deltoid tuberosity

-Lower extremity: as proximal on the thigh near the gluteal fold as possible

-Limb occlusion: each person requires an individualized pressure for effective use of BFR. Literature suggests that a cuff pumped up to 7/10 perceived tightness has been most effective to allow arterial inflow and occlude venous outflow- however, use manual palpation of the radial or brachial artery to ensure arterial blood flow is not occluded. Best practice would be to use a Doppler ultrasound device to ensure arterial blood flow is not occluded.

Exercise recommendations

- Repetitions The typical protocol seen throughout current literature is training with BFR for 4 total sets. The first set is of 30 repetitions, followed by 3 sets of 15 repetitions.

- Load should be around 20-30% of your maximum weight—training at a higher percentage has not been shown to yield further benefit

- Rest period 30-60 seconds between sets, without releasing occlusion

- See the evidence-based recommendations below (Scott et al., 2014)

Troubleshooting

You should not be experiencing pain prior to initiating exercise—if this is the case the wraps are likely too tight. The discomfort experienced with BFR should be due to the buildup of metabolites, not the cuff pressure. If you are not able to complete the 30-15-15-15 repetition protocol then either the load you are using is too high or the cuff occlusion is too tight. Check that you are using the 20-30% max load and then assuming the load is correct, loosen the cuffs.

Recap

To wrap it all up here—combining BFR with low load resistance training exercises improves muscle hypertrophy and strength, and has important implications for individuals who are not able to train using heavy load.

Using BFR to rehab

If you are interested in learning more about blood flow restriction or incorporating it into your rehabilitation program, schedule an initial evaluation with one of the therapists at Evolution Sports for thorough and individualized care to return you to doing what you love!

References

- Scott et al., 2014. Exercise with Blood Flow Restriction: An Updated Evidence-Based Approach for Enhanced Muscular Development. Sports Med. DOI 10.1007/s40279-014-0288-1

- Slysz J, et al. The efficacy of blood flow restricted exercise: A systematic review & meta-analysis. Journal of Science & Medicine in Sport . 2016; 19: 669-675.

- Cook CJ, Kilduff LP, Beaven CM. Improving strength and power in trained athletes with 3 weeks of occlusion training. Int J Sports Physiol Perform. 2014;9(1):166–72.

- Loenneke JP, Thiebaud RS, Abe T, et al. Blood flow restriction pressure recommendations: the hormesis hypothesis. Med Hypotheses. 2014;82(5):623–6.

- Luebbers PE, Fry AC, Kriley LM, et al. The effects of a seven- week practical blood flow restriction program on well-trained collegiate athletes. J Strength Cond Res. 2014;28(8):2270.

- Loenneke JP, Fahs CA, Rossow LM, et al. Effects of cuff width on arterial occlusion: implications for blood flow restricted exercise. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2012;112(8):2903–12.

- Loenneke JP, Kim D, Fahs CA, et al. Effects of exercise with and without different degrees of blood flow restriction on torque and muscle activation. Muscle Nerve. Epub 2014 Sep 3. doi:10.1002/ mus.24448.

- Kubota A, Sakuraba K, Koh S, et al. Blood flow restriction by low compressive force prevents disuse muscular weakness. J Sci Med Sport. 2011;14(2):95–9.

- Soto GA, et al. The Effects of Short-Term Resistance Training with & without Blood Flow Restriction on Neuromuscular Adaptations. International Journal of Exercise Science . 2017. 2(9): Article 14

- Nielsen JL, Aagaard P, Bech RD, et al. Proliferation of myogenic stem cells in human skeletal muscle in response to low-load resistance training with blood flow restriction. J Physiol. 2012;590(Pt 17):4351–61.

- Ozaki H, Sakamaki M, Yasuda T, et al. Increases in thigh muscle volume and strength by walk training with leg blood flow reduction in older participants. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66(3):257–63.

- Takarada Y, Takazawa H, Sato Y, Takebayashi S, Tanaka Y, and Ishii N. Effects of resistance exercise combined with moderate vascular occlusion on muscle function in humans. J Appl Physiol 88: 2097–2106, 2000.

- Takarada Y, Nakamura Y, Aruga S, Onda T,Miyazaki S, and Ishii N. Rapid increase in plasma growth hormone after low-intensity resistance exercise with vascular occlusion. J Appl Physiol 88: 61–65, 2000.